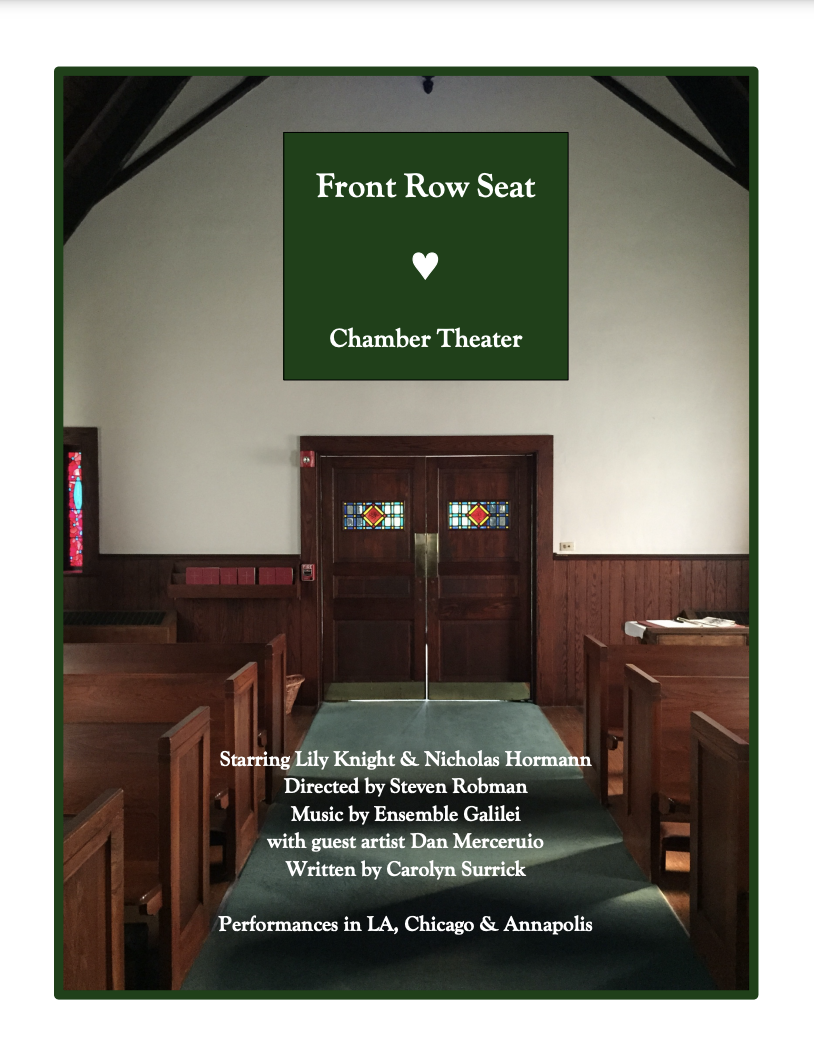

Front Row Seat

Rarely is a Chamber Theater production so deeply collaborative and infused with the energy and insights of the whole company - Front Row Seat is just that. This tale of the survival of a small church in Baltimore started as a book, became a play, and was brought forth in a series of workshops in 2023. With legendary actors Lily Knight and Nicholas Hormann, shaped by Steve Robman, one of the most innovative and successful directors of new plays in Los Angeles, and graced with some of the finest Irish musicians in America, this new work by Carolyn Surrick is a remarkable (and beautiful) look at the nature of faith and community in 2020, as the pandemic and political instability darkened the world.

Front Row Seat – The Process

Chamber Theater.

A term new to me, our director, Steve Robman first suggested that this could best describe Front Row Seat. It’s not exactly a play, not exactly a tone poem performed by two actors, and not exactly a musical in spite of the addition of five musicians to the company.

It could have been a play, but there is no scenery, there are no costumes or props, and the actors are seated for most of the show, with their books on music stands in front of them. It might be a musical, except the actors never sing. It started out life as an austere tone poem, with lute and viola da gamba, but then the script changed, and a new musical vocabulary was needed as it was workshopped in LA in the first months 2023.

Front Row Seat started out life as a book of poetry. Pastor Stewart Lucas, my partner in crime at a small church in Baltimore, asked me to write about the events of 2020. He thought that in fifty years, people might want to know how we survived, and how our congregation was able to stay in community during a worldwide pandemic. It was not the first time that I had been asked to document our shared experiences, and I gladly accepted the challenge.

Some months later I delivered the book to his office. He started reading it, looked up and said, “But where is George Floyd? Where is Trump? Where is the election?” He had meant the whole world, not just our little corner.

I went back to my desk to create a comprehensive look at the year. I read every sermon. Looked at every newsletter. Started researching names, dates, and places. I put together a three-ring binder of the events from the year, with selected sermons, all the newsletters, and the poetry. It took months. When it was finally finished we made copies and gave them to any parishioner interested reading, and then willing to participate in a focus group.

It was fascinating. We found that because of the events of 2020 – Covid, the lockdown, George Floyd’s murder, Black Lives Matter, the political climate, and then the election in November - no one, not a single person, had a clear picture of what happened that year, and when. The shock of a pandemic life had distorted time - the tragedies and the joyous moments.

A few months later, Pastor Stewart took a job outside of Atlanta and the book was headed for the closet, to be buried among other archival relics. I sent a copy to our producer, Lindsey Nelson in LA, who gave a copy to Steve Robman who thought it might have some promise as a theatrical production, and we were on our way.

There were many, many pages to delete. Then there were lines to be written. Scenes needed to be added. And in the following months, the words, the feeling, the shape, and indeed the emotional content started to change.

The room itself was a marvel of collaboration. Steve Robman had been at the Yale Drama School with actor Nicholas Hormann. Lily Knight and I went to the same pre-school in Baltimore in the 1960’s. Julie Haber, our stage manager, also an alum of the Yale Drama School, had worked with everyone in theater at some time or another, and our infinitely supportive and observant producer, had faith in us and the process, and unwavering patience.

The relationships were so long and so deep, and the trust so absolute, that there was indeed only one goal – to create a fine piece of art that could speak clearly and eloquently to our shared experience.

Should we delete that page? Oh, yeah.

Do we need to add more clarity on page 84? Of course.

What about an Overture? Perhaps.

It’s the middle of October, 2023, and we’re really close. There is a rehearsal with actors in LA coming up. The musicians just met in Chicago. We’ll all be together in early November and then we’ll try it out in front of an audience. We’ll see if they laugh, and cry. We’ll know what works and what does not, and then we’ll be in a room together again, together, deleting and sculpting – finding the words and music to remind our audience of what many of us thought we would rather forget. And we may all find that the memory of the small graces of 2020 are more powerful than the fear, the rage, and the sorrow.

“You’re kidding, right? Five musicians?”

Ensemble Galilei has been rocking words and music for twenty-some years. We started with NPR’s Neal Conan as our narrator for a winter solstice concert in the early 2000’s, went on the partner with the Hubble Space Telescope Institute and The National Geographic Society, and collaborated with the Metropolitan Museum of Art. More recently Neal Conan and Anne Garrels joined our merry troupe for Between War and Here – poetry and memoir about the men and women who go to war and then come back, different.

When we started working on Front Row Seat, the text was austere, the accompanying instruments were a viola da gamba and a lute, and the music held a sacred place. But then, everything changed. The music no longer fit. The soundscape needed to be broader because the play had become more expressive, more dramatic.

There was much work to be done on the script as we moved through rehearsals and we needed a person dedicated to thinking about the music - where, what, and how? Our trusted producer, Dan Merceruio, was available (who has shaped Ensemble Galilei’s recordings for over a decade). Who would the musicians be, and why?

Those are easy questions to answer. Collaboration is complicated, made more complicated with every living person added to a room. Efficiency is helpful. If the people sitting in the circle have thousands of tunes in their heads, no one is rifling through stacks of sheet music, or going online to find and then print out five copies of something that might not even work in the end. But more than efficiency, and more than existing as a living-breathing library of traditional music, and more than being really smart and easy going, among these five people, there’s a shared respect, a cumulative history, and joy in both the creative spark and the follow-through.

We don’t need these musicians to bring down the house for this show. We are not giving each player a moment to shine. We are taking the ridiculous fire-power of these five musicians sitting on the stage, and we are creating something bigger than any one of us.

When Jesse brings forth a sonic field that supports Lily’s meditation on what church does and why it’s important – he’s doing it with such grace and understatement that it is almost invisible, yet it expansively illuminates the meaning of the text. When Isaac picks up the pipes at the end of Act One, with his extraordinary capacity to dive deep, he reminds the audience of the emotional content of all that has just happened, reinforcing the despair in a way that only he can do. What is he playing at that moment? He made it up. He created it on the spot because it was just right. Do we need Jackie? Do we really need banjo and bodhran, two of the most hated instruments in Irish music (according to him)? He is never a soloist. He’s never driving the dramatic energy forward. Yes, we do. Because, in those places in the music where there is joy, he shapes it. The viola da gamba? It is the ground upon which the actors and the musicians can stand.

And about that singer. One of my favorite moments was when our director, Steve Robman, turned to me and said, “When exactly did you decide that we needed a singer?” To which I replied, “You were there.” In our very first rehearsal with this band in March, I asked Dan to sing a verse of I Want Jesus to Walk with Me, just so we could all hear the tune with the words. But when he did it, everything in the room changed. We were all swept away by the intention and effortless commitment in his voice. No, there was not a plan for a singer before that moment but the way that his musical presence changed the play was monumental.

So yes, there are five of us. Yes, our backgrounds are not in church music. Yes, this is not like playing in a bar in Chicago on a Thursday night, or playing in a concert hall that seats twelve hundred people, or even like playing in a small church on a Sunday morning. This is like going to work with two of the finest actors on the planet, with a director who really knows what he’s doing, and the play’s producer, Lindsey Nelson, the who will happily say, “Sure, let’s add Dan!”

Five musicians committed to working together, and creating something extraordinary, who know how to be brilliant, invisible, and transcendent.